I remember my vet school classmate, Jess, also pregnant in our fourth year, sneaking into the ultrasound room to scan her own baby. She elbowed me, conspiratorially, grinning, wanting me to go too. I couldn’t imagine doing it, reflexive rules follower, but also something else: a feeling that it would be shameful, disrespectful, like digging up a seed to check if it was germinating.

Vet school was a kingdom of women. There were only a handful of men in our class of eighty-something. Now, I am surrounded by males. Husband, partner, two enormous sons who like to puff out their chests and loom over me, grinning. I’m alone here, it often feels. The stable, unwavering line of their physiologies, while mine rolls through, lifting and then lowering me, driving me first outward, expansive, and then retracting back, pulling a hood deep around me.

I think about a talk I went to once, about the creatures that live deep in the sea, in the unchanging dark, high pressure. Yeti crabs, waving their fluffy mittens in the scalding water of hydrothermal vents. The lecturer said that these creatures are often called extremophiles, because the conditions in which they live are unimaginable to us. But, he said, actually these crabs are in some ways the opposite of extreme; their environment does not vary. There are no tides, seasons, or even day and night for them. Just an utterly stable, undeviating, endless present. This is how I think of men, stably cruising along at a steady altitude of testosterone. I read an article about the clinical trials for a birth control pill for men. The trial was called off when too many of the men became suicidal. It seemed the fluctuating hormones where too destabilizing to their psyches. When this hit the news, I saw a lot of women both crowing and lamenting online that women have grimly borne pill-induced severe mood disruptions for decades and no one said a thing. But one boy says he wants to die and we abandon the entire project. I got that, and also saw it differently. Men are like Yeti crabs, adapted to the unchanging, level arrow flight of their hormones. Their minds and bodies need this steady drip. Women’s minds and bodies are adapted to change, to circle, to be lifted up, over and down and around again, crest and trough in turn. Men subjected to the same go crazy. It is understandable. They are not built for this churn.

What is on the other side of all this rounded lifting and falling? Maybe I already know. Maybe I’m already on the far side of the peak. Last month, when I found blood in my underwear, it seemed early. I consulted my calendar and found that yes, this period was following only three weeks after the previous one. I had expected them to gradually grow farther apart, and then quietly fade away, but I looked it up and found out that often periods stack closer together as the hormones flag. I had a sensation of something coming up behind me, closing in, footsteps picking up their pace behind me in the dark. The word came to me and the irony trailed behind it: quickening. Or like a sound Dopplering, compressing and approaching. What will happen once it passes me by—the sound elongating and distorting as it fades, and then what? Stillness? A no longer useable uterus, a stable, uncycling level? What will that be like, the blank smell of snow?

The compression, the ramping up of the ramp down was reminding me of something, the analogy nagging. At the sink one morning, I realized, it was labor. Contractions spaced out at first, manageable, then amping up and closing on each other, my head disappearing between each cresting wave, utterly unsustainable by definition. “The only positive feedback loop in physiology,” my physiology professor had told us.

I have a stack of papers with no where to go, after cleaning out Pat’s house. We’d hired a company to liquidate all her possessions, but their policy was to set aside any “personal effects” — photos, mementos — so we’d done a sweep of everything ourselves, before they came in to cart away the impersonal effects. In a closet, under a box of Christmas ornaments, there was a little manila mailer addressed to her, containing the results of a workup for infertility: “Illness: trying to get pregnant x 6 years.” They’d put her under, puffed up her abdomen with carbon dioxide, peered around at everything, shot little jets of indigo carmine through her uterus and watched it bloom out the ends of her Fallopian tubes. Everything is in order, little Mrs., they reported. She’d tried for six years to get pregnant, then had Sean, and then tried another six years, her dream of a big family ticking down for a decade and a half. Here was this tidy packet of results in distant, paternalistic, clinical language, the report she kept for her whole life, that issued the devastating news: there is nothing wrong with you.

I talked with her once, about menopause. About what it’s like. She had a tendency to dip briefly into subjects like a swallow dropping to a lake surface, and then veering away. “You miss it, when it’s gone,” she said. And then we moved on to other topics.

This week, I went to see the Bob Dylan movie in the theater, with all my various boys. After about an hour, I found myself bored and irritated. This is often a sign that I am watching a Boy Movie. These are films featuring a lone genius on a hero’s journey, fending off villains, enemies, and stodgy sticks-in-the-mud as he alone, clear-sighted, true vector of the future, strides forward. The women in the Bob Dylan movie are cardboard cutouts, with only a partial, and grudging, exception made for Joan Baez. Elle Fanning’s character, Sylvie, is meant to be the real life Suze Rotolo, I guess, of the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan fame, but drained of everything but being hot and a bitch and a serious drag on Bob. I was on an unexpected emotional journey with her character. You see, at some point, long ago, I read that the woman snuggled against his shoulder on that album cover was a nothing, a rando, just some bitch he happened to be sleeping with that week who sort of elbowed her way into the pictures. So, as I watched the movie, I had one of those angry moments when you realize you’ve been lied to by misogynists, and you believed them. So here was her reputation being rehabilitated; in the movie, her character is more than a rando he hooked up with a couple times! But then, in the movie, she turns out to be a drag and a shrew who nags and aggravates Bob and is too provincial to understand his genius. One time she’s shown in a paint-smeared button-down as she leans out the window, hotly, as Bob yells up from astride his cool motorcycle in the street. Whatever dumb girl painting she was working on is never shown, and we cut to her clutching his waist as they ride to Newport for Bob to meet his destiny. Suspicious of this portrayal, I got home from the movie and read up about actual Suze Rotolo. She’d taught him about civil rights and social justice movements, about Bertolt Brecht and Rimbaud. He’d run all his songs by her and pined away while she was in Italy for months. None of this makes it into the movie.

It took me a full day to bring myself to look up Toshi Seeger, wife of Pete, who is physically omnipresent in the movie, but says about three sentences. She just seems to trail around after her husband, gazing inscrutably, half-Japanesely, at things. I almost expected someone on screen to ask who’s this lady always just standing around while important men did important things? “Oh, that?” Pete would say, “That’s Yoko Ono, my emotional support animal.” Sure enough, when I googled Toshi Seeger, I discovered she was a major big deal.

The movie makes the mistake of seeking a plotline in a human life, and then laying it retrospectively onto the past. Bob Dylan, well on his way to legend/icon status at twenty one, must have been making only the right moves, only what a genius would do. If it looks like he’s being sulky or mean, that’s because you’re on a plane far beneath him and you don’t get it. He was never being petulant and surly simply because he was a very young man, but because petulance was necessary and correct in a way only a lone genius would understand. Plenty of shots of Dylan framed in doorways, brooding, wreathed in smoke. I was thinking about this essay by Simon Critchley, in which he writes, “Life doesn’t need a narrative arc. We don’t have to be the stories we endlessly tell and retell about ourselves. Those stories are fabulation and — if told too often — falsification.”

I’m tired of the hero’s journey and boy movies, with their linearity and start, middle, end. I’m in circular time, cycling, female time. I just finished reading Fear of Flying; in it, Isadora says something like, “Menstruation is always sad.” Even when you are fervently, desperately hoping not to be pregnant, it’s still sad, the blood. Something that might have been now definitively isn’t. And then the whole thing starts again.

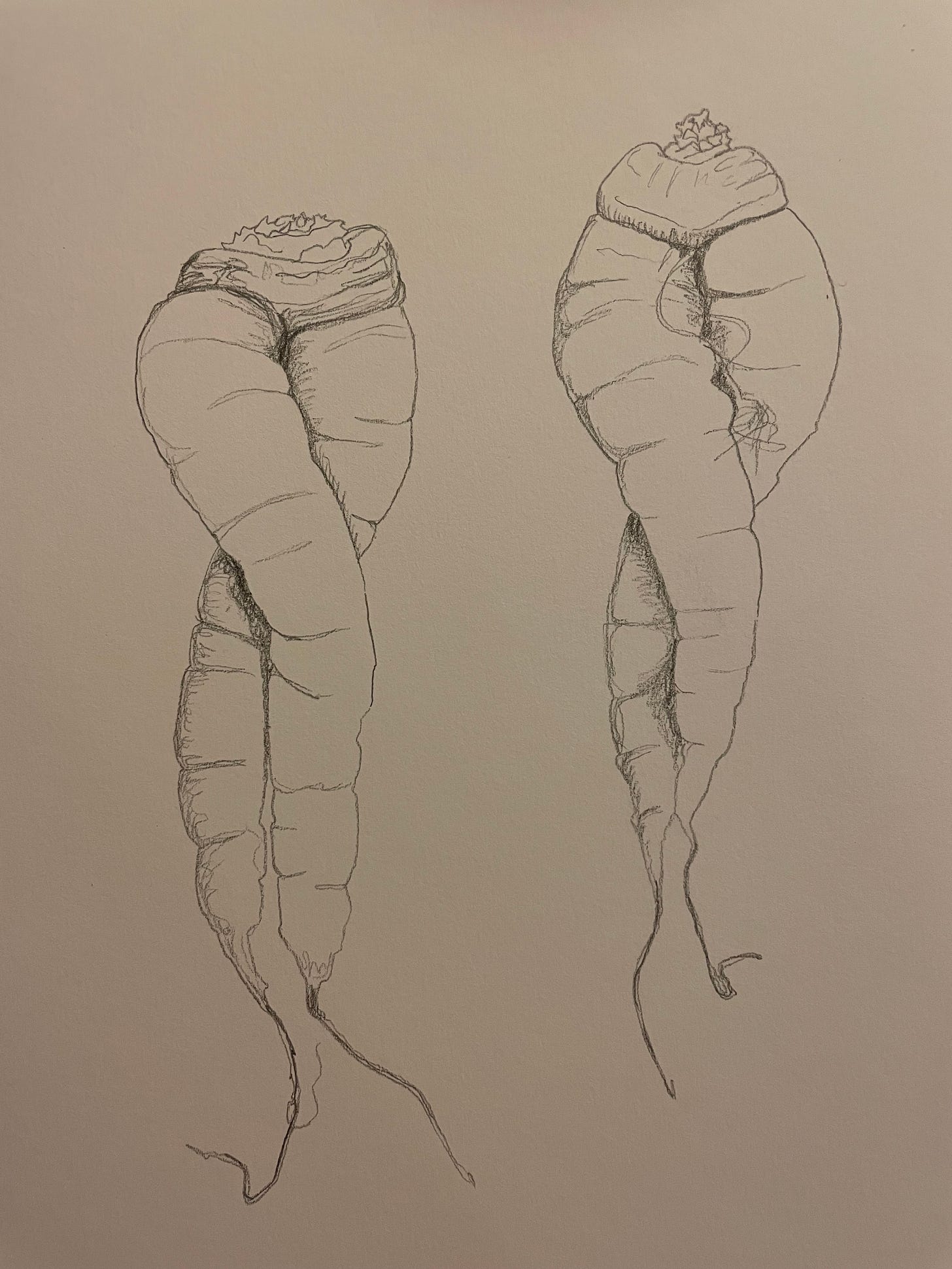

At the end of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Shunryu Suzuki wrote, “Nothing exists but momentarily in its present form and color. One thing flows into another and cannot be grasped. Before the rain stops we hear a bird. Even under the heavy snow we see snowdrops and some new growth. In the East I saw rhubarb already. In Japan in the spring we eat cucumbers.” It reminds me of a thing we used to say all the time in the 90s: “That’s so random,” like things were supposed to cohere and make sense have a plot. Not just be one thing and then another thing and that’s how life is. But that is how life is.

There was a musician who could be a real dick and he made a lot of excellent songs. There was a woman who tried to get pregnant for years. One time, she did. Then for many more years, she didn’t again. Sometimes she was happy, sometimes angry. One time she was so tired and overwhelmed and frustrated she burst into rare tears at the sight of a line of ants traversing the bathroom floor. She worked for a long time and then retired. Her husband died. Then later she died, and this little manila folder passed into my hands. This manila envelope with a medical report from 1977, this slim packet of grief tucked away in a closet, listing procedures, evoking phrases like “an unlubricated speculum is introduced…”— it didn’t, it doesn’t, mean anything. That sounds bad, but it isn’t bad.