Universal and specific

every little thing

It might be my only memory from second grade: Mrs. Randall, a fox in the 80s vernacular, her flocculent perm teased away from her face, which I cannot remember except that it was young and beautiful. Her dress, broad-shouldered, tapering to a waist cinched in a wide, red, vinyl belt, one hand holding a book while the other was raised in the air as she labored to translate, on the fly, a poem from Greek to English. She teetered on a word in the middle of a line spoken from the perspective of a rose, warning off a would-be rose-picker, “if you do…” Mrs. Randall said, “I will…” and that’s where she paused, her free hand miming a closing and opening motion, grasping at the word and the rose in her mind “…embroider your hand in red.”

I must have puzzled over that moment over and over, because it lodged in my head. I wondered, at the time, why she hadn’t picked an easier word to get the point across. Why not just say “I’ll make your hand red”? It would make sense and keep things moving. But for all my practical thinking, something about the specificity of the word embroider stayed with me. And something about Mrs. Randall searching for that word, unwilling to settle for one that might have come more quickly, but that failed to convey her native Greek to a bunch of seven year olds.

Why this memory? Why keep this and not anything else from second grade, except maybe the sight of a banner hung by some teachers outside their colleague’s classroom that read, “Lordy lordy, Murray’s 40!” It was some combination of how extremely old 40 seemed to me then, and the rhymy music of it, and the strangeness of the expression (“lordy” not being common parlance in the Irish/French Canadian Massachusetts mill town of my youth). I was fascinated by words already by then, much more than by people. Among people, the adults interested me much more than my peers.

My only memories of 3rd grade are a few scrap-like recollections of my teacher, Mrs. Low, who everyone said was an actual witch who wore rings on her toes. She loved whales, and I made a shoebox diorama of many whale species made to scale and suspended from the ceiling of the box with string.

I have since learned that there are multiple types of memory. The kind that remembers what happened, or episodic memory, is weak in me. I don’t remember much of what happens to me, and plotlines of books and movies disappear from my mind completely in a matter of months. It’s hard to make sense of the past, as a result. I can’t track a throughline or a sense of story because I remember so little. Just these fragmentary moments, unconnected to anything else I remember, glimpsed with my characteristic tunnelled vision, focused tight and at close range— a chunk of mica, a caterpillar on a weed growing through a sidewalk crack, a dead snake with its belly scales turned up to the sky.

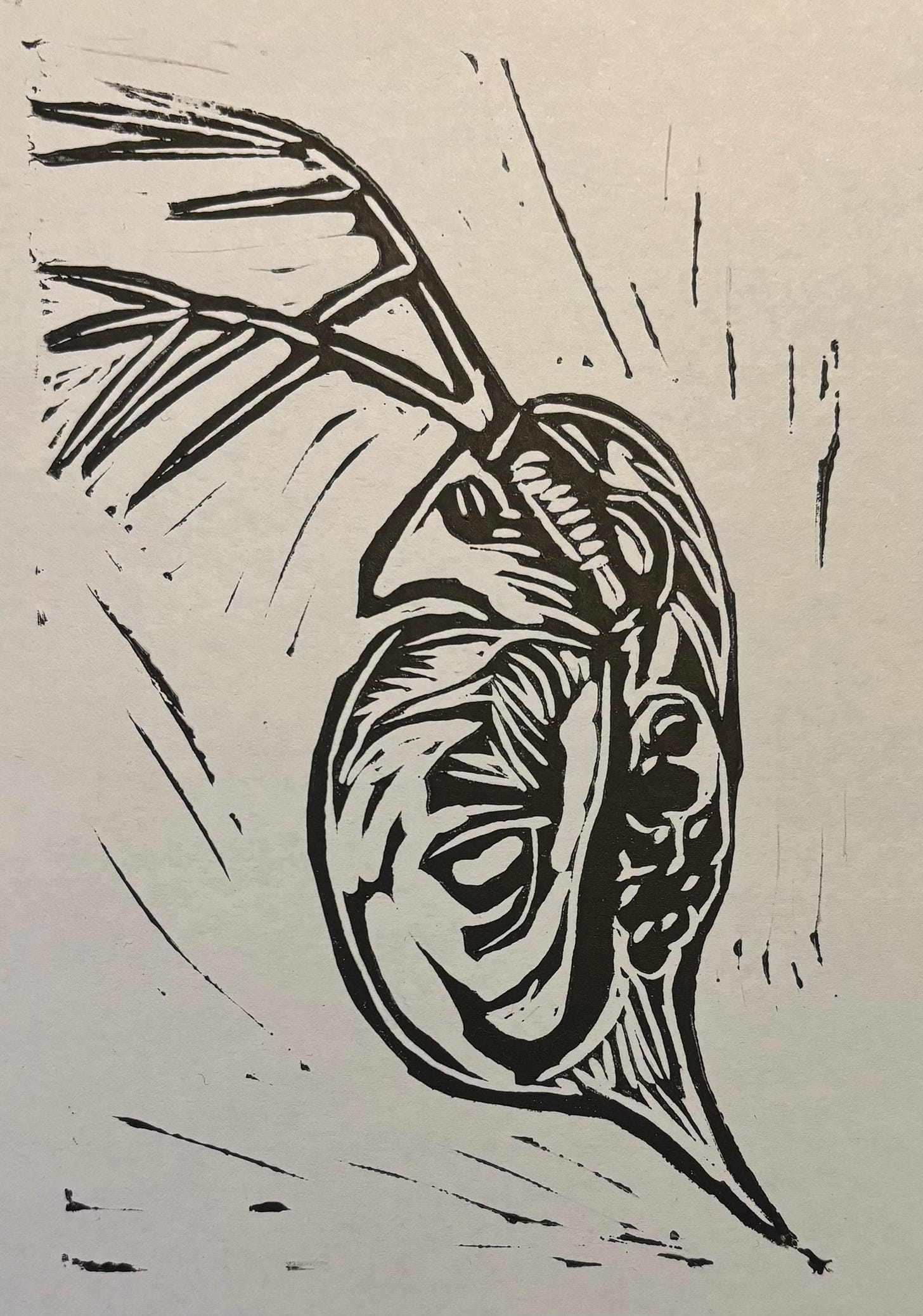

My drawing teacher in a class I took a few years ago told us it’s not about whether we make a “good” drawing, it’s whether or not we produce a specific line. That’s not the same as a line that best reproduces the shape of the thing being depicted. It means a line that isn’t vague, generic, or bland.

Adrien Brody said in a recent interview, “a lack of specificity can get you more work in a leading man’s space, but it is the specificity of character that makes human beings so interesting.”

I was reading an article about microplastics, and how each of us has a disposable spoon’s worth of it lodged here and there in our brains. The article talked about how scientists are trying to figure out if this is harmful. I think we could instead decide to consider it unacceptably rude to put plastic spoons in people’s brains and not do it.

One of my students came home from a trip to Chicago in March where they dye the river green for St. Patrick’s Day. He showed me pictures, and said he read that the dye is “harmless, non-toxic" but was it really? And I said it’s rude to dump green dye in someone’s house, even if you tell them all the while, “it’s not harmful!!! It won’t hurt you!” The thing is, I don’t want green dye all over my house, and I don’t want plastic spoons in anyone’s brains, regardless of demonstrable harm.

The students are thinking about this ever since we read Max Liboiron’s Pollution is Colonialism. There’s a part in the book where Liboiron talks about research they do on fish in maritime Canada, and whether and how much plastic those fish ingest. Some fish eat a lot of plastic, and others very little. Silver hake, for example, don’t seem to eat much of it. Liboiron writes about how many environmentally-minded folks wrote to them, upset, saying that we mustn’t tell anyone that some fish don’t have plastic in their guts, because then people will think there’s not a problem here. Their idea seemed to be that the only way to get anything done about anything is to convince people that everything is relentlessly bad, that every single living thing is suffering clearly documented “harm” and that’s why we have to act. If word gets out that silver hake don’t eat much plastic, even though cod do, then we will have no chance at changing anything.

I admit that I felt something a little similar when I read a paper about the effect of ocean acidification in tiny, shelled organisms. I used the paper as the basis for my job talk for my current teaching position. The paper made me uneasy at the time, because it showed that these particular little guys don’t seem perturbed by the shifting pH of the water around them. No awful and vivid stories of their calcium carbonate shells fizzing and dissolving until their soft bodies float loose and exposed — on the contrary, they seemed to handle it fine, and what’s more, their usual shell building activities pump more acid in the microenvironment right around them. Foraminiferans and radiolarians, tiny, unimaginably numerous plankton seemed, on the whole, to be doing…ok? “Oh great,” I thought, “more fodder for people to claim climate change is not that bad.” It bothered me that I couldn’t point to clear and present dangers in every single case. It felt like, short of that, we’d never be able to convince anyone to do anything. Then the students and I read Liboiron and other Indigenous thinkers, and more essays and articles, and watched movies, and we found ourselves thinking all the time about this messed up system that forces people to prove harm using science and statistics before they can object to anything. We were shifting to some form of remedial understanding of being in “good relations” with everything around us, and some behaviors are simply rude. Some behaviors put you outside right relationships and you really ought to fix that. Just because the silver hake don’t eat the plastic doesn’t mean it’s fine to dump it in their house, and if you do spill it there, you should clean it up, not just tell the hake to prove legal damages or show their medical bills. I took to saying “this is like the silver hake” whenever we saw this approach at work in the world—in stories about poisoned farms in West Virginia, and a bunch of “hysterical Hispanic housewives” in Tucson.

I imagined a band called “Silver Hake and the Radiolarians,” its members all the organisms that can’t prove harm done, but would, if they could, probably sing songs that point out to us that, regardless, they’d really rather we not do these things, and could we please stop simply because it’s bothering them.

Under the current circumstances of fascist dismantling of the federal government, it seems quaint to think of a time when we were speaking in higher education about the wisdom and benefit, or lack thereof, of content/trigger warnings on readings and other materials. Not surprisingly, this government is coming for the students, and also not surprisingly, most of the discourse is focused on the rarefied Ivies and other exclusive institutions, even though pretty much everyone goes someplace other than those. I teach at a community college, and a lot of the stuff in the media about colleges pertains to us, and a lot doesn’t. It’s not something I really am going to get into here. My point is about trigger warnings. I don’t use them, and it’s not because I teach science, or because community college students haven’t been hurt, or because I don’t care if students get upset. The thing about trigger warnings that renders them fairly useless is that they’re not specific enough.

When you put a little disclaimer on an assignment about rape, or suicide, or pregnancy loss, it’s fine to do, but it’s not going to help, not really. The idea of trigger warnings, I think, is to allow students to avoid being plunged into the perpetual now of a traumatic memory — the sudden reliving of whatever happened, not as memory, but in a bodily sense, as if it’s still happening. I have seen students slip into this state. I recognize the slack-jaw, the stillness of the body, the unfocused eyes. What causes it is never what you would expect. Most of the time, they don’t say anything about it, and eventually they come back to where we are. Sometimes they will say a little bit, like “when things come up suddenly on my left side, peripheral vision—it reminds me of something.” Sometimes they tell me more than that. I could never predict the idiosyncratic things that trip them into these memories, no more than I can predict them in myself. I could never warn them all about the million little things that might do it— a smell, a texture, a pattern of stitching on a jacket that reminds you of a jacket your face was pressed up close to while something happened.

I was getting a massage a couple weeks ago, and when he lifted and rolled me up onto my side, I slid not just elsewhere in time and space, but into another body entirely—the movement reminded me so vividly of shifting Pat’s body up on her side to clean her bedsore, and somehow it was like I had a bodily memory of not only doing that motion, but receiving it, being in her body as I cared for it. How could I ever get a trigger warning that that might happen?

I was listening to some meditation instructions the other day, about not judging anything to be either “good” or “bad” — to neither cling nor avoid. The teacher said there’s nothing that everyone, universally, would agree is good, and nothing we would all agree is bad, so they can’t be objective categories, but more a matter of perspective. I mean, I guess. But most of us would be pretty upset if our cat or our kid got run over by a car in front of our very eyes. But yeah, not totally universal, I guess.

What did I read somewhere, about essays being the form where the writer takes something very specific, and broadens it to connect to the universal. Or was it about poetry? Or maybe it was fiction. Maybe just effective communication is always like that. But then again, what could be less universal than poetry?

At night I read to Christophe from this big anthology of poems. We generally don’t say anything about the poems, but the other night, I read “A Spiral Notebook” by Ted Kooser. My eyes welled up and I suppressed the roughness in my voice to get through it, and at the end, Christophe said, “That sounds like a typical MFA workshop poem. Like, the classic, ‘write about an object…’ prompt.” I came to, from whatever the poem had worked in me.

Reading the New Yorker, I usually skip the poems because the magazine’s taste seems not to be much like mine, but the other day, I tried out “Midnight Nest” by Arthur Sze. I felt little as I read up through these lines:

a squirrel runs along the top of a redwood fence -- not ideas about ourselves, but ourselves, radiant, in our bodies-- you peel an orange, and a mist rises into the air-- sandpipers scurry along a tawny beach--

and then, the poem having barely registered in me, I read the next line:

“I peel an orange, and a mist rises into the air—”

And I felt a physical sensation of dropping into a chair with a thud, from a great, airy fairy height, into a corporeal reality, in a chair opposite Arthur Sze, in a backyard bounded by a redwood fence, both of us peeling oranges as he regarded me. He’d lulled me with that narcissistic poet’s trick of using “you” when he really means “I” and of using “our” when he really means “my” and of using “ourselves” when he really means “myself.” I thought he’d meant you-as-I and now I discovered he’d actually meant you-as-me and I-as-I. Now I found myself peeling an orange, pierced by a sense of being perceived by this man, looking at me as I peeled the orange. I squirmed and also felt astonished, like I’d been singled out by a magician or a stand-up comic doing crowd work.

For a while, humanities departments were touting some research that English majors have greater empathy because reading so many people’s stories builds our capacity to imagine ourselves into someone else’s skin. Of course, this then got distorted, or at least crabbed and boxed up as a “soft skill” desirable in corporate America, and as a reason why we should therefore still allow English majoring. I know it was a move toward self-preservation; it’s not like English professors actually think marketability is important. But also, empathy isn’t really that important. There are plenty of other ways to attend to someone, and to attune to them without feeling what they feel. I, for one, feel mostly an emotional blank while I talk to people. After I am alone again, I eventually get some feelings leaking in, slowly, and gradually I might figure out what I feel. This actually makes me unusually adept at listening to people and helping them, because I am not distracted by my own feelings about what they say. I explained this to someone the other day, and they wrinkled their nose up and furrowed their brow, as if to say, “How terrible, how inhuman.” Not much I can do to convince anyone otherwise, if they think that. The fact is, I am always trying to help everyone, and I consider insects, and leeches, and oak trees to all be someones, as well as people. Aid the hake, the cod, the radiolarian. Aid the leech, the juniper, the caddisfly. Each one specific, and I am not particular.